The opening montage is pretty good: It lets us know we’re in a future where the possession of fuel is of supreme importance (not too distant a future, apparently), and we see some newsreel-like footage of how the world got to this point, as well as some clips from a movie called Mad Max (The Road Warrior is a sequel, although that term hardly seems appropriate). This intro, with narration, is in standard movie ratio: The screen is squarish. Things are fairly ordinary until the moment after the screen goes black, and suddenly we get blown backward out of a car’s supercharger and the screen whomps into widescreen Panavision and we’re doing about eighty or ninety miles an hour down the highway of the Wasteland. I think it’s safe to say that not a single “fairly ordinary” thing happens after this.

Mad Max was Australia’s biggest hit ever, although it didn’t do much over here in the States (in Seattle, it had a brief run at the Grand Illusion; also a showing in a UW Australian film series, where some members of the audience absolutely refused to believe that such a not-nice movie was the most popular film Down Under). It’s a good movie, but it didn’t come near suggesting the kind of cosmic blowout that the same director/co-writer had in store for the sequel. The Road Warrior (it’s just Mad Max II in Australia; too bad) is a stunning, witty, riveting story about finding meaning in a world that seems meaningless, and how the action of finding that meaning becomes the stuff of legend. Key word here is “Action,” because that’s what The Road Warrior is, as well as what it’s about (Raiders of the Lost Ark looks like a game of bridge by comparison). George Miller has invoked a rollercoaster ride in describing the film’s headlong rush, and that will serve as an approximation of the movement of The Road Warrior.

But it doesn’t begin to do justice to the kind of vaulting imagination seen at work here. A simple tale: A man must lead people and their cargo to safety against incredible odds. But as the narrative hits you (and hits you, and hits you), the richness of invention along the way is breathtaking. Just naming cinematic comparisons, one could bring up Kurosawa, Peckinpah, Huston, and Spielberg; that might give some idea of the flavor of the movie, but it should be stressed that this is a George Miller film all the way, and is quite free of any hommages to the masters. Miller simply has an understanding of the way movies move, and with his big budget here, he is able to take the care that was sometimes absent in Mad Max. (A number of shots – most of which last only a few seconds – look like the kind of things that filmmakers spend their whole day waiting to get. I don’t know how Miller did it so often.)

No idea what The Road Warrior‘s post-Festival fate will be (it’s entirely possible that when Warner Brothers releases it in August, it’ll get dumped in the toolies as a typical summer action movie), but if it comes to your town, don’t miss it. There are few things as exhilarating as running through and surviving the Wasteland.

First published in The Informer, May 1982

Odd review; I don’t say much about what actually happens onscreen, and neglect to mention the name of the movie’s little-known leading man. This was part of a package of reviews of movies shown in the Seattle International Film Festival that year, published in The Informer, the Seattle Film Society’s newsletter, of which I was editor. I had forgotten that the film showed at SIFF well before it opened for its regular run. The SIFF founders had the volume cranked up way too high (as was their preference) at the Egyptian theater, and the movie pretty much took the roof off. I realize this must have been before the Film Society (separate from SIFF) had the bright idea to bring Mad Max back for a couple of showings, which sold out in spectacular form.

Posted by roberthorton

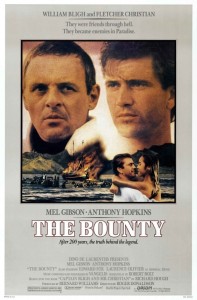

Posted by roberthorton  The Bounty

The Bounty W

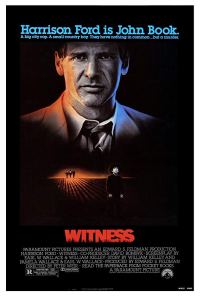

W It should come as no surprise that leading foreign directors inevitably gravitate toward America; there’s still no better place to make movies if you want the most sophisticated technicians and equipment, not to mention actors.

It should come as no surprise that leading foreign directors inevitably gravitate toward America; there’s still no better place to make movies if you want the most sophisticated technicians and equipment, not to mention actors. With Witness, you know right off the bat you’re in mysterious Peter Weir country. The sense of unidentifiable strangeness that Weir can convey so well is present in the early scenes in a Pennsylvania Amish community, which has not updated itself in a century.

With Witness, you know right off the bat you’re in mysterious Peter Weir country. The sense of unidentifiable strangeness that Weir can convey so well is present in the early scenes in a Pennsylvania Amish community, which has not updated itself in a century.