After receiving lukewarm reviews during its opening back East a few weeks ago, Street Smart is getting an equally lukewarm national release by Cannon Films. Actually, it’s a good deal more interesting than your average movie fare, although it’s not too difficult to understand why Cannon is shying away from the film.

For one thing, the hero (Christopher Reeve) is a weasely reporter who invents an important story, lies to a courtroom, and cheats on his devoted girlfriend. Not the most attractive figure, yet the film makes something interesting out of this guy.

His story chronicles a day in the life of a New York pimp. It makes the cover of an important magazine, wins great applause, and earns Reeve a television contract with a local station. The twist is that everyone assumes the story is based on a certain notorious pimp (Morgan Freeman) who is currently up on murder charges. Soon the lawyers are ordering Reeve to hand over his non-existent notes and other evidence that might be relevant to the case, while the violent Freeman hatches a plot that draws Reeve even deeper into an ethical swamp.

Street Smart takes some chances by exploring the tarnished hero’s fall. Reeve haunts the low-life streets long after his story is published, and gets romantically involved with a prostitute (very well played by Kathy Baker), to the consternation of his girlfriend (Mimi Rogers).

Most of this stays on the intriguing level, because director Jerry Schatzberg (Scarecrow) doesn’t take the Reeve character to the limit. Reeve is good at portraying the necessary moral shiftiness, but he can’t quite embody or explain the real darkness that must be somewhere in this character.

Schatzberg gets an edginess to many of the street scenes, and every scene that Baker is in has a heartfelt authenticity. This movie is almost a sleeper; file it away for future video rental.

There’s not much need to file the weekend’s other opening, The Gate. It’s a clean-cut horror movie, about a horrible hole that opens up in a suburban backyard while mom and dad are away for a couple of days. The kids do battle with the demons that come up out of this thing.

It’s mostly an excuse for a lot of pretty good special effects. The demons consist of a great many whitish gnomes and homunculi, plus one big poobah demon who could, but for some reason doesn’t, kill the diminutive hero (Stephen Dorff).

There’s some attempt by director Tibor Takacs to suggest the complacency of America’s backyards, and the shady secrets they might conceal. But that angle was much better essayed in the recent The Stepfather, and The Gate can’t match the chilliness of that film.

First published in The Herald, May 1987

Street Smart launched Morgan Freeman into a new realm, that’s for sure. The Gate was Dorff’s first feature film; its director has had an interesting career, and writer Michael Nankin has gone on to a profitable run, mostly in TV.

Posted by roberthorton

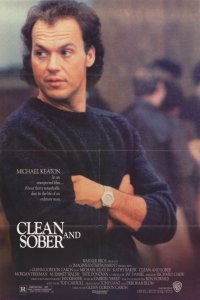

Posted by roberthorton  Long, uneven, and perhaps oversimplified, Clean and Sober is nevertheless a strong and affecting movie, the kind that gives you the sense that, when the end credits roll, you’ve been through some kind of real journey.

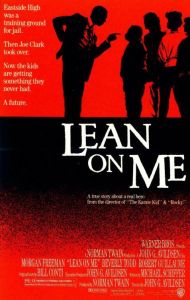

Long, uneven, and perhaps oversimplified, Clean and Sober is nevertheless a strong and affecting movie, the kind that gives you the sense that, when the end credits roll, you’ve been through some kind of real journey. Lean on Me is based on the life of Joe Clark, the high school principal who took over a seething New Jersey school and whipped it into shape through an unbending belief in discipline. Clark was loved by some and despised by others, all of which made for juicy headlines a couple of years ago. (You may remember the image of Clark on the school steps, brandishing a bullhorn and a baseball bat).

Lean on Me is based on the life of Joe Clark, the high school principal who took over a seething New Jersey school and whipped it into shape through an unbending belief in discipline. Clark was loved by some and despised by others, all of which made for juicy headlines a couple of years ago. (You may remember the image of Clark on the school steps, brandishing a bullhorn and a baseball bat). Glory recounts the true story of a

Glory recounts the true story of a