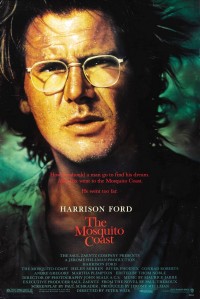

Early on in The Mosquito Coast, someone refers to Allie Fox, a brilliant, intense and slightly off-center inventor, as a Dr. Frankenstein who creates mechanical monsters. Specifically, Fox makes refrigeration devices, machines for making ice.

Early on in The Mosquito Coast, someone refers to Allie Fox, a brilliant, intense and slightly off-center inventor, as a Dr. Frankenstein who creates mechanical monsters. Specifically, Fox makes refrigeration devices, machines for making ice.

But, as The Mosquito Coast makes clear as it goes along, Fox will create a real Frankenstein monster in the course of the film: himself. This is the story of a man’s descent into tyranny and madness; it is a dark character study, and, in some ways, a monster movie.

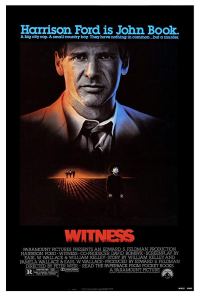

It’s the latest from the Witness team of Harrison Ford (who plays Fox) and director Peter Weir. Paul Schrader, a filmmaker drawn to monomaniacal figures (Taxi Driver, Mishima) adapted the screenplay from the novel by Paul Theroux.

Theroux’s story is narrated by Fox’s son, an adolescent boy (River Phoenix, of Stand by Me), who tells of the most traumatic adventure in his family’s life. Frustrated with a lack of success among the American philistines, Allie Fox decides to cart his family to the jungle, a Central American nowhere called the Mosquito Coast.

Once there, Fox buys an entire town, which turns out to be a cluster of shacks, miles upriver from civilization, which the jungle threatens to overtake. He, his wife (Helen Mirren), and their two sons and two daughters begin to clean up, and – with the aid of natives – bring a semblance of civilization to the spot.

Fox’s greatest achievement, however, will be building a giant refrigerator – to bring ice to people who have never seen such a thing. This is his obsession.

The second half of the film brings a series of disasters, and the comic tone of Fox’s eccentricity gives way to real madness, including telling his children they cannot go back to the United States because nuclear bombs have been dropped there.

This role is obviously Harrison Ford’s chanciest performance. He looks right for it – his hair longish and pulled back, his eyes squinting behind metal-rimmed glasses. And Ford’s acting is good, but at the same time he seems fundamentally miscast. The epic rage and megalomania of the role don’t come naturally to him, and when his character really wigs out, it seems forced. (Jack Nicholson was reportedly an early choice, which sounds appropriate, and this character does resemble Nicholson’s mad family man from The Shining.)

There’s a clunky quality to the plot, which moves and lingers at unexpected locales, and the intrusion of three banditos at a crucial point smells like a contrivance.

This film has been taking a critical hammering since it opened in New York and Los Angeles a couple of weeks ago, and probably it belongs in the “ambitious failure” category. But those are the best kind of failures to have, and some of Weir’s dreamy images (photographed by John Seale, who also shot Witness) will stay with you. An isolated spit where Fox vows to make a final stand looks like a surreal end of the world, and the river journey that ends the film has some beauty.

Hanging over Weir’s work is the ghost of German director Werner Herzog, who made two films about white men who go to the South American jungles on an insane quest and go mad (Aguirre, The Wrath of God and Fitzcarraldo). The Mosquito Coast is uncannily reminiscent of those films at times, and one wonders whether Herzog might have made a more inspired, visionary, wacko film out of this story. But then, he already did.

First published in the Herald, December 1986

I see there’s going to be a long-form TV adaptation of the book, featuring Justin Theroux, the nephew of Paul. So its time has come, perhaps. Whatever you think of the movie, it’s interesting that it exists at all, given the subject matter; presumably, without Harrison Ford’s clout, this project would’ve ended up in the dustbin that holds all those other interesting but far too risky ideas. Andre Gregory and Martha Plimpton are in the film, and so is Jason Alexander. And Butterfly McQueen? Wow. My memory tells me that River Phoenix carries the movie; at this point it was clear that he was an unusual kid, more than capable of holding the center of a big film.

Posted by roberthorton

Posted by roberthorton  It should come as no surprise that leading foreign directors inevitably gravitate toward America; there’s still no better place to make movies if you want the most sophisticated technicians and equipment, not to mention actors.

It should come as no surprise that leading foreign directors inevitably gravitate toward America; there’s still no better place to make movies if you want the most sophisticated technicians and equipment, not to mention actors. With Witness, you know right off the bat you’re in mysterious Peter Weir country. The sense of unidentifiable strangeness that Weir can convey so well is present in the early scenes in a Pennsylvania Amish community, which has not updated itself in a century.

With Witness, you know right off the bat you’re in mysterious Peter Weir country. The sense of unidentifiable strangeness that Weir can convey so well is present in the early scenes in a Pennsylvania Amish community, which has not updated itself in a century.