Advance reports suggested that the film version of The Clan of the Cave Bear might be among the most laughable goofs of recent memory—evidently preview audiences were hooting at the film, and Warner Bros. has been postponing the release since it was first announced for last summer.

Advance reports suggested that the film version of The Clan of the Cave Bear might be among the most laughable goofs of recent memory—evidently preview audiences were hooting at the film, and Warner Bros. has been postponing the release since it was first announced for last summer.

The movie arrived a few days ago (without an advance screening for the press, often a bad harbinger). As it turns out, it’s not as inept or as ludicrous as had been rumored.

It’s not particularly good, mind you, but it’s certainly not Heaven’s Gate among the cavemen. Or should we say cavepeople, since the film projects a post-feminist attitude upon the hapless Neanderthals.

I’m one of the last English speaking people to have avoided Jean M. Auel’s book, but I assume this feminist theme is carried on from the source material. It has been adapted for film by John Sayles, who often writes screenplays for hire so he can finance his own, self-directed movies (The Return of the Secaucus Seven, Brother from Another Planet).

I hope Sayles makes something good from the fee he got for Cave Bear, because there’s certainly not much of him in it. Sayles’ gift for dialogue is, understandably, not in evidence, since the characters speak in grunts and hand signs (there are subtitles and narration).

The story is barely there: About 35,000 years ago, a young, blonde-haired tyke named Ayla, whom we are to understand is Cro-Magnon, is picked up by a band of dark, hairy Neanderthals and brought into their clan by a witch doctor (James Remar) and a medicine woman (Pamela Reed). The little girl is raised by these sympathetic people until she becomes the long-legged Daryl Hannah (from Splash), who shows early signs of wanting to play with weapons, heretofore a male domain.

Her struggles are primarily with a mean boy (Thomas G. Waites), an early espouser of the Playboy philosophy, who will someday lead the tribe. He wants her thrown out of the cave, and she must kneel in his presence and submit to his sexual needs. Only the men are allowed to hunt, and the women provide them with food. Jeez, these guys are really Neanderthals.

Ayla becomes the first feminist when she finds a slingshot and starts aiming stones at a stump of wood, which begins her journey toward self-sufficiency.

The film is really not that awful. But it seems there are some stories that can be conjured up in prose that can’t be similarly treated in movies, and this is one of them. It’s tough to believe the gorgeous Hannah (who is otherwise pretty good) as a Cro-Magnon woman who will someday evolve into modern man. She’s already there, even if she doesn’t shave her legs.

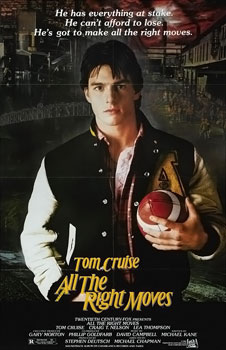

Michael Chapman, the former cinematographer whose only previous film as director was All the Right Moves, gives everything a respectful, ordinary gloss. However, there’s an exciting scene in which the young chieftains battle an enormous bear, and the bear is one of the greatest I’ve ever seen in the movies.

One question: if Ayla brought her proto-feminist ways to bear on such an early form of human civilization, how did we fall so far behind again in the succeeding 35,000 years? I guess we’ll have to look to the sequels to find out.

First published in the Herald, February 12, 1986

No sequel would there be for the movie series, thanks to this film’s reception. And when I say “Heaven’s Gate for cavemen,” I don’t mean Heaven’s Gate was bad, but that Heaven’s Gate was the standard for big-scale flops. Although I suppose if we apply the latter definition this movie was the Heaven’s Gate for cavemen.

Posted by roberthorton

Posted by roberthorton