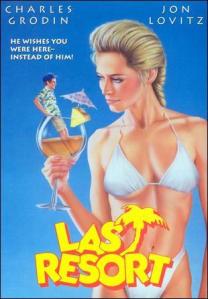

Last Resort is based on a familiar comic idea: the nightmare vacation. In this case, a tired businessman (Charles Grodin) takes his family to a resort called Club Sand on a Grenada-like island in the Caribbean, where a civil war seems to be taking place

Last Resort is based on a familiar comic idea: the nightmare vacation. In this case, a tired businessman (Charles Grodin) takes his family to a resort called Club Sand on a Grenada-like island in the Caribbean, where a civil war seems to be taking place

But that’s the least of the problems. When they arrive on the island after a hair-raising plane ride, the family can’t understand why the beach is surrounded by barbed wire and soldiers. And the resort’s cabins are in various states of disintegration which, since the walls are apparently made of plywood, is a serious situation.

The staff is a multinational band of sex-crazed kids (they teach the vacationers the traditional island game called “Show Us Your Breasts”). Both Grodin’s teenage children are seduced by the locals, and his pre-pubescent son is carted off to a mini-camp where the director is into Nazi power games.

All of which would seem to leave a lot of room for comedy. But the low-budget Last Resort is awfully low on laughs, even though it sets up a few good situations and Grodin goes through his usual (often amusing) shtick.

Robin Pearson Rose is funny as Grodin’s wife, who eats psychedelic mushrooms and thinks she’s a horse. And Jon Lovitz, a regular on Saturday Night Live (he’s the guy who lies, hilariously) plays a bartender who can’t get his language straight, prompting a couple of precious moments.

But most of the film, and Zane Buzby’s direction, caters to Grodin’s method of slow-burn reaction, during which a series of outrageous atrocities happen to him while he keeps a steady deadpan. I like Grodin, although his comic style tends to make you smile dryly rather than laugh out loud. The film, by following his lead, is fitfully amusing without ever breaking out.

That, in itself, is OK. But Buzby’s direction, and the script by Steve Zacharias and Jeff Buhai (Revenge of the Nerds) doesn’t take time to give the characters much background. And a number of plot points, such as the fling Grodin’s oldest son has with a local entertainer, are never resolved.

The whole idea of the island’s revolution might have been made more central, which could have made the film an even blacker comedy. It’s a subject for some fiendishly clever filmmaker to exploit, given the Central American situation. As it is, the idea is set up early but not used until the end, when the revolution provides a convenient climax but not much else.

The perverse use of the civil war might have made Last Resort and original comedy. Instead, it satisfies itself with a familiar situation, where the gags are as isolated as the island itself.

First published in the Herald, April 17, 1986

A review written in haste, it would seem. Zane Buzby acts in the film as well, and is notable for her performance as the droning waitress taking Jerry Lewis’s order in Lewis’s Cracking Up. The cast includes a bunch of people soon to become better known, including Phil Hartman, Megan Mullally, and Mario Van Peebles.

Posted by roberthorton

Posted by roberthorton  Against All Odds is another of those sweaty, hot looking movies that builds up a great sense of atmosphere. It may be that the director was too busy whipping up this atmosphere to notice that the movie was coming unglued, because Against All Odds is a rambling piece of work that succeeds neither as a love story nor as a thriller. It bears scant resemblance to the 1947 film on which it is based, Out of the Past, directed by Jacques Tourneur. That film was a lean, hard story about a guy with a past, a shady deal and a bad girl. It hurtled toward the hero’s eventual doom with efficiency and terseness.

Against All Odds is another of those sweaty, hot looking movies that builds up a great sense of atmosphere. It may be that the director was too busy whipping up this atmosphere to notice that the movie was coming unglued, because Against All Odds is a rambling piece of work that succeeds neither as a love story nor as a thriller. It bears scant resemblance to the 1947 film on which it is based, Out of the Past, directed by Jacques Tourneur. That film was a lean, hard story about a guy with a past, a shady deal and a bad girl. It hurtled toward the hero’s eventual doom with efficiency and terseness. A real old-fashioned movie-movie, Chances Are is a welcome addition to the dismal Hollywood scene. It’s not a great film, but it is refreshing to see a traditional comedy format being smartly reworked by people who seem to care about the material.

A real old-fashioned movie-movie, Chances Are is a welcome addition to the dismal Hollywood scene. It’s not a great film, but it is refreshing to see a traditional comedy format being smartly reworked by people who seem to care about the material. The Deceivers is loaded with elements that suggest its worthiness as a movie property. It’s got scale, pageantry, action. There’s nothing here to prevent a rousing tale along the lines of Gunga Din.

The Deceivers is loaded with elements that suggest its worthiness as a movie property. It’s got scale, pageantry, action. There’s nothing here to prevent a rousing tale along the lines of Gunga Din. In the opening shots of A Dry White Season, two little boys wrestle happily on a bright green lawn. One boy is white, the other is black. This may seem like an ordinary enough image, but the fact that the boys live in South Africa immediately charges the scene with bitterness.

In the opening shots of A Dry White Season, two little boys wrestle happily on a bright green lawn. One boy is white, the other is black. This may seem like an ordinary enough image, but the fact that the boys live in South Africa immediately charges the scene with bitterness. Blake Edwards must be plenty tired of A Fine Mess by now. First the screenplay bounced around for a few years, searching for the right casting, at one point slated as a Burt Reynolds-Richard Pryor teaming.

Blake Edwards must be plenty tired of A Fine Mess by now. First the screenplay bounced around for a few years, searching for the right casting, at one point slated as a Burt Reynolds-Richard Pryor teaming. Overheard while walking out of the theater after Firestarter: “Let that be a lesson to you: never volunteer for scientific experiments.” Words of wisdom. But if people, real or fictional, ever heeded that lesson, we’d be robbed of a lot of science fiction/horror stories.

Overheard while walking out of the theater after Firestarter: “Let that be a lesson to you: never volunteer for scientific experiments.” Words of wisdom. But if people, real or fictional, ever heeded that lesson, we’d be robbed of a lot of science fiction/horror stories.