The original 1958 version of The Blob was a typical low-budget sci-fi movie of the period: There was very little to distinguish it aside from its relatively snappy pace and the presence of an intriguing young actor, “Steven” McQueen. In most respects, it was like a hundred other wonderfully goofy monster movies in that golden era of flying saucers and giant insects.

The original 1958 version of The Blob was a typical low-budget sci-fi movie of the period: There was very little to distinguish it aside from its relatively snappy pace and the presence of an intriguing young actor, “Steven” McQueen. In most respects, it was like a hundred other wonderfully goofy monster movies in that golden era of flying saucers and giant insects.

And yet, somehow, you gotta love that blob. So simple. So direct. So gooey.

I suppose there are people who appreciate the blob, and people who don’t. The latter are probably beyond help; for the former, there’s a brand-new version of The Blob, featuring a much higher budget than the original and with state-of-the-art special effects. But still with the same basic idea.

Once again, the blob falls from outer space and attaches itself to the hand of an expendable old coot. Then it begins devouring everything in sight, starting with the coot, until an entire small town in threatened.

The only people who can stop the blob are a motorcycle boy (Kevin Dillon) and a cheerleader (Shawnee Smith), but of course they have a hard time getting anyone to believe them.

The director is Chuck Russell, who displayed an inventive visual sense in his previous film (A Nightmare on Elm Street 3). Russell has a field day concocting ways for the purplish-pink mass of blob to surprise its victims; one person is yanked down a drainpipe, another is squished in a telephone booth, and a romantic teen is unfortunately surprised during a heavy-petting session in lovers’ lane.

Russell includes an update on the original film’s most famous scene, in which the blob slimed its way into a movie theater. In this case, however, the original is not improved upon. One twist in the new version provides an explanation of the blob’s origin. It isn’t just a bit of space glub; actually, the blob is the result of a government germ-warfare test. When the officials hit town, they’re more concerned with capturing the blob than with saving the populace; “This’ll put U.S. defense years ahead of the Russians,” burbles one scientist.

This new Blob is a good little horror movie There’s some comfort in the thought that, despite its one-dimensional personality, the blob is still gooey after all these years.

First published in the Herald, August 1988

Russell went on to direct The Mask and Eraser; he wrote the screenplay with Frank Darabont, then at the beginning of his career. Certainly a movie headlined by Kevin Dillon and Shawnee Smith has some essential 80s cred, am I right? As far as I know this film’s rep is pretty solid with horror mavens—and the ’58 Blob is not exactly a fall-down masterpiece, so there’s not a great deal to resent about a sequel.

Posted by roberthorton

Posted by roberthorton  In 1985, a giddy, extravagantly gruesome horror movie called Re–Animator brought a rookie director named Stuart Gordon to the spotlight. Actually, Gordon had been a director for years, in the vanguard of experimental live theater in Chicago. His first movie displayed considerable wit, iconoclasm, and a freewheeling willingness to disgust.

In 1985, a giddy, extravagantly gruesome horror movie called Re–Animator brought a rookie director named Stuart Gordon to the spotlight. Actually, Gordon had been a director for years, in the vanguard of experimental live theater in Chicago. His first movie displayed considerable wit, iconoclasm, and a freewheeling willingness to disgust. Really good ghost stories are hard to come by these days. Oh, there are plenty of horror films, but the ghost story is a specific genre, with definite rules and traditions. A new film, Lady In White, fulfills so many of these traditions that it’s tempting to applaud it. Too bad it isn’t a better movie.

Really good ghost stories are hard to come by these days. Oh, there are plenty of horror films, but the ghost story is a specific genre, with definite rules and traditions. A new film, Lady In White, fulfills so many of these traditions that it’s tempting to applaud it. Too bad it isn’t a better movie. Last year’s A Nightmare on Elm Street was a flat out screamfest, a niftily constructed thriller that raised gooseflesh more honestly and effectively than any horror film since The Shining. Its carefully balanced mingling of dream and reality had helpless audiences unsure where the next scare was going to come from.

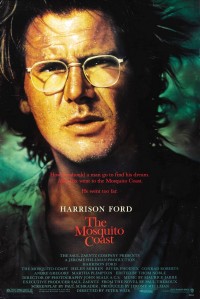

Last year’s A Nightmare on Elm Street was a flat out screamfest, a niftily constructed thriller that raised gooseflesh more honestly and effectively than any horror film since The Shining. Its carefully balanced mingling of dream and reality had helpless audiences unsure where the next scare was going to come from. Early on in The Mosquito Coast, someone refers to Allie Fox, a brilliant, intense and slightly off-center inventor, as a Dr. Frankenstein who creates mechanical monsters. Specifically, Fox makes refrigeration devices, machines for making ice.

Early on in The Mosquito Coast, someone refers to Allie Fox, a brilliant, intense and slightly off-center inventor, as a Dr. Frankenstein who creates mechanical monsters. Specifically, Fox makes refrigeration devices, machines for making ice. If you’ve never seen

If you’ve never seen  Once the financial take reached a certain level, there was no avoiding a sequel to

Once the financial take reached a certain level, there was no avoiding a sequel to