Marge Hills is the sort of character in novels who stares out the window a lot and wonders why interesting things always seem to happen to other people, while she is stuck in her dreary, workaday existence. Except that The Good Wife, a mood piece set in 1939 Australia in which Marge is the titular character, isn’t a novel, it’s a movie.

One of the problems with the film is that it never quite finds a way to make Marge’s issue alive in cinematic terms. In pages of description, a novel can vividly portray spiritual suffocation. A movie must come up with images to show the same thing, and The Good Wife hasn’t found them.

What is has found is a good performance from the heretofore wooden Rachel Ward, the gorgeous star of The Thorn Birds and Against All Odds. Her lean face holds all the texture of a thousand hours spent looking out into the arid Australian afternoon.

In screenwriter Peter Kenna’s scheme, she will find a change in her dull life through sexual curiosity. Her husband (Bryan Brown, also Ward’s real-life husband), is one of those rough-hewn laborer types; he engages in, shall we say, uncomplicated lovemaking. It’s not enough for Marge, and she looks to his brother (Steven Vidler) for a different approach.

Actually, the brother turns out to be as unsatisfactory. Then a city slicker (Sam Neill, the smooth Soviet of Amerika) arrives, to take over the bartending job at the town hotel, and also to cut a romantic swath through the town’s womenfolk. Marge is both repulsed and attracted to this rake, and she makes him the focus of her attention – to the lip-smacking interest of the gossipy locals.

The situation is well into D.H. Lawrence territory, but oddly without any dark sensuousness. The oppressive dustiness of the atmosphere seems to seep into the characters, and director Ken Cameron’s style is so dry that Marge’s obsession doesn’t really catch fire.

The film comes close to acknowledging this. When someone points out to Marge that she’s wasting her time chasing after the ne’er-do-well bartender, she looks lost and says, “He must be able to love me, or what would be the point of my feeling like this? It wouldn’t make sense.” It doesn’t, quite, and even Ward’s sensitive, wearied performance can’t bring it convincingly into focus.

First published in The Herald, February 24, 1987

I must have watched the TV miniseries Amerika, but I don’t recall it. Just from reading this description, it seems obvious Neill should’ve played the husband and Brown the rakish bartender, but maybe Brown already had the script for Cocktail sitting around, so who knows. (That one came out a year after The Good Wife.) Director Cameron worked a lot in Aussie TV; screenwriter Kenna died this year this came out. Original title: The Umbrella Woman.

Posted by roberthorton

Posted by roberthorton

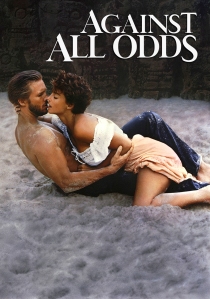

Against All Odds is another of those sweaty, hot looking movies that builds up a great sense of atmosphere. It may be that the director was too busy whipping up this atmosphere to notice that the movie was coming unglued, because Against All Odds is a rambling piece of work that succeeds neither as a love story nor as a thriller. It bears scant resemblance to the 1947 film on which it is based, Out of the Past, directed by Jacques Tourneur. That film was a lean, hard story about a guy with a past, a shady deal and a bad girl. It hurtled toward the hero’s eventual doom with efficiency and terseness.

Against All Odds is another of those sweaty, hot looking movies that builds up a great sense of atmosphere. It may be that the director was too busy whipping up this atmosphere to notice that the movie was coming unglued, because Against All Odds is a rambling piece of work that succeeds neither as a love story nor as a thriller. It bears scant resemblance to the 1947 film on which it is based, Out of the Past, directed by Jacques Tourneur. That film was a lean, hard story about a guy with a past, a shady deal and a bad girl. It hurtled toward the hero’s eventual doom with efficiency and terseness.