With the Academy Award nominations coming up Wednesday, film distributors are jockeying their releases to get optimum tie-in publicity. That’s why Ironweed, with its presumably obligatory nominations for Jack Nicholson and Meryl Streep, is opening this weekend; that’s why The Whales of August is here. Small or difficult or serious movies open nationally now, hoping to get a boost from the Oscar picks.

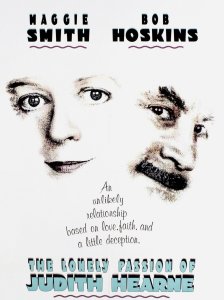

Which brings us to The Lonely Passion of Judith Hearne, and Maggie Smith. Maggie Smith epitomizes what the Academy loves about acting: She’s cultured, she’s classy, she’s English. Of course, she’s also a gifted actress, which helps, but that’s not the only criterion for winning an Oscar. Whatever Smith has, it has won her two statuettes (Best Actress for The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, 1969; Best Supporting Actress for California Suite, 1977) and three other nominations.

The Lonely Passion of Judith Hearne is Maggie Smith’s latest bid, and it may well be recognized by the Academy; it’s a meaty role in an eminently Anglo story. Judith Hearne is another of Smith’s spinsters, a bright, disappointed woman who gives music lessons as a means of surviving. There’s a yearning within her that isn’t satisfied, however. Clue to her character: a mother complaining that her child isn’t learning enough because Judith plays too much during the lesson.

The film, adapted from the novel by Brian Moore, picks up Judith’s character just as she moves into a new rooming house in Dublin in the mid-1950s. The landlady (Marie Kean) is something of a shrike, whose son (the exceedingly perverse Ian McNeice) is a grotesque, lazy poet. The main attraction in the household in the landlady’s brother, James (Bob Hoskins).

He’s just returned to Ireland after 30 years in New York City. To Judith, he carries all the allure of someone who’s been somewhere and done things, and she’s rapt at his tales of America.

Their quasi-courtship is the center of the film, and Smith and Hoskins are a lovely match. Smith’s leanness and lined face contract nicely with Hoskins’ burly energy. James is a hustler, and most of his interest in Judith lies in his mistaken belief that she has money – money that might be invested in his going scheme, a fast-food place where Dubliners can buy American food.

The tentative and eventually sad relationship has possibilities that aren’t fully served by Jack Clayton’s direction. Clayton surfaces every few years to bring his literary approach to bear; his recent films include the extremely disappointing adaptations of The Great Gatsby and Something Wicked This Way Comes.

Clayton gives Judith Hearne a tasteful surface, but he can’t reach the source of Judith’s loneliness. The film’s central tandem, while fine, deserve better.

First published in The Herald, February 11, 1988

It did not bag any Oscar nominations that year, despite my wariness. A marvelous cast in place, and the final performance by Marie Kean, who, by the way, had a beefy batting average; she appeared in fewer than 20 big-screen films, but they included Barry Lyndon (she’s Barry’s mum), The Dead, Ryan’s Daughter, Neil Jordan’s Angel, and Cul-de-Sac.